Taking the ringdown route to understanding the humans of science

What follows is an attempt to process and understand Cassandra Willyard’s post on Last Word on Nothing, about her preferring the humanised stories of science over the stories of the science itself (“Physics writers, this is how you nab the physics haters — human emotion”; my previous post on this is here). He words have been weighing on my mind – as they have been on others’ – because of the specific issues that they explored: humanising the process of science, and to be able to look at all science stories through the humanised lens. By humanising the process of science, it’s not that the science takes a backseat; instead, the centrepiece of the story is the human. Creating such stories is obviously not a problem for/to anyone. The problems come to be when, per the second issue, people start obsessing over such stories.

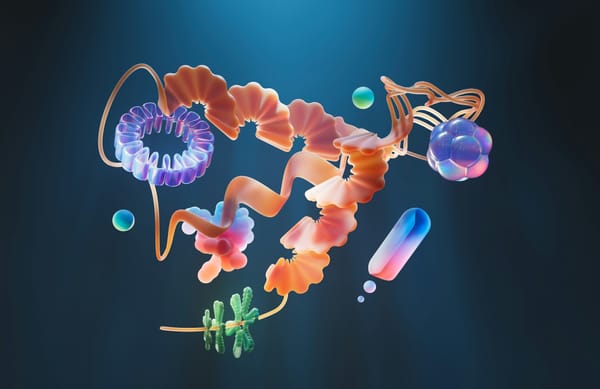

At this point, I’m not speaking for anyone but myself; nor is my post written in the usual upside-down pyramid style, rather the other way round. Second: I deviate significantly from Willyard’s post’s demesne because I’m just following my thoughts-current on the subject. I’m tempted to use a metaphor: that of the ringdown, the phase when two blackholes that have merged settle down into a stable, unified shape.

I

By virtue of not being about people, or humans in general, science stories without the human component are a hard-sell. Willyard’s right when she says that humans are interested in stories about other humans – but I think what she’s taking for granted here is that humans being interested only in stories about other humans is fair. It’s definitely tenable, but is it fair? The sense of fairness in this context emerges from the idea that it’s not okay for us to consume – while we’re alive the one time we are – only that which immediately affects us. Instead, we must make room for the truly wonderful, and identify and appreciate the kinds of beauty that transcend utility, that would be beautiful from all points of view and not just our own.

If such appreciation had been shared by all consumers of journalism, then producing pure-science stories would be a breeze. But in reality, it’s anything but. This is why advocating for the persistent humanisation of science is almost offensive: humanised science sells very well; it does not need a shot in the arm, nor a platform like Last Word on Nothing, to help its cause. It is an economically privileged form of science journalism that has no right to complain.

To be sure, Willyard is neither calling for the persistent humanisation of science nor is she complaining that humanised stories of science are not the norm. That said, however, I feel that she is downplaying the importance of non-humanised science stories from a very pragmatic perspective: her grounds are that they’re not emotional enough – which suggests she’s saying that emotions are important. Why? Emotions are easy to market; emotions are easy tools of interpersonal communication, especially ones that can transcend language, culture and enterprise.

A part of my indignation towards her post emerges from this endpoint: the axiomatic inference that that which lacks emotions is unimportant, and that such a suggestion disparages an entire branch of science communication that seeks to explore science without simultaneously exploring the human condition. What also contributes to my sentiment being what it is is the fact that Willyard is a science journalist – she’s one of us – and for her to make such distinctions, for her to declare such preferences without also exploring their underlying economics, feels like she’s being either myopic or selfish.

(I must clarify that though I’ve used big words like ‘selfish’, I’m feeling them in a more diluted form.)

II

Humanised science is almost populist as well. In India, many newsrooms publish such stories without having to call it science, and they don’t. They’re disguised as ‘science and society’, ‘science policy’, ‘higher education’, ‘public administration’, etc. You, my reader, consume these kinds of science stories regularly, without having to be lured into the copy or being given extra incentives. You’re definitely interested.

… except for one small genre of the whole thing: pure science, the substrate on which all else that you’re reading about is founded, but which has over time become sidelined, ostracised into the ‘Other’, the freak show reserved for nerds and geeks, the thing which scares you without making you question that fear. (“I’m scared of math! I gave up working with numbers a long time ago.” Why the actual fuck? “No idea. I see an equation and I’m just scared.”)

The reason I’m so riled up (which I didn’t realise until I began writing this sentence – and that’s why I write this blog) was something I recently discussed with my friend O.A. at a party organised by The Wire. That was when I’d first heard about C.P. Snow’s ‘two cultures’ essay, which O.A. mentioned in the context of a spate of news reports discussing hydrological issues in agriculture.

O.A. said, “People don’t understand how water works in agriculture. I read something about someone trying to estimate how much water a crop uses in a season and then, with that information, trying to determine how much water we’re losing across our borders when we export that crop to other countries. The whole method is so stupid.” (This conversation happened a few months ago, so I’m rephrasing/paraphrasing.)

It really is stupid: evaluating agriculture – even when at the level of a single crop sown in one reason in a single acre of land – in terms of just one of the resources it utilises makes no sense. Moreover, the water used to grow a crop does not rest in the produce; it seeps into the soil, runs off, evaporates, it reenters our local ecosystems in so many ways. What made this ‘analysis’ stupider was that (a) it appeared in a leading business daily and (b) the analyst was a senior bureaucrat of some kind.

O.A. went on to describe a fundamental disconnection between the language of India’s policymakers and the language of India’s farmers and labourers, a disconnection he said was only symptomatic of the former’s broad-brushstroke ideas being so far removed from the material substance of the enterprises they were responsible for regulating. He then provided some other examples: fuel subsidies for fishermen, petroleum distribution, solar power grid-feeding, etc.

This kind of disconnection comes to be when you know more about the logistics of a product or service than about how its physical nature defines its abilities and limitations. And more often than not, investigations of this physical nature neither require nor benefit from having their ‘stories’ humanised. There are so many natural wonders that populate the world we engage with, that have quietly but surely revolutionised our lives in many ways, whose potential to enhance–

III

Fuck, there I go, thinking about the universe in terms of humans. I concede that it’s a very fine line to inhabit – exploring our universe without thinking about humans… Maybe I should just get it out of my system: without understanding how the universe works, we as a species cannot hope to forever improve our quality of life; and, disconcertingly, this includes the act of being awed by natural beauty! It’s like Joey’s challenge to Phoebe in Friends: “There are no selfless acts.”

BUT we first do need to understand how the universe works in non-human, non-utilitarian terms. Asking if such a thing is even possible is a legitimate question but I also think that’s a separate conversation. We consume the pure science that we do because it’s what caught someone else’s fancy, it’s what a scientific journal is pushing in our faces, it’s what a scientist is thinking about in a well-funded research lab in the First World. There are many biases to overcome before we can truly claim to be in the presence of unadulterated/unmitigated beauty, before we can have that conversation about whether objective beauty really exists. However, the way to begin would be by acknowledging these biases exist and working to overcome them.

To those asking why should we at all – I’d have said “we should because I think so, and it’s up to you to trust me or not”, but I don’t because a lot of science writers around the world feel the same way, which means we have something in common. I don’t know what this something is but, thanks to the wellspring of responses Willyard’s post received, I know that I must find out.

Finally, I know that Willyard’s post doesn’t preclude all these possibilities. It simply asks that we get those uninterested in physics to give a damn by using the humans of physics as a conduit of interestingness. After all, the human condition may be a vanishingly small part of the cosmic condition that we partake of, that we have used to construct civilisation, and everything else out there may be cold, cold space – but humans are the way the universe examines itself.

My reservations exist in a very specific context: that of science journalism in India, specifically the India of pseudoscience, fake news, caste conflicts and broken education. In this context, I’m constantly anxious about becoming a selloff – a writer who gives up someday and trades his conviction in the power of pure science to help us think more clearly about our fraught communities and governments off in exchange for easy career progression.

fin.

Featured image: A simulation showing a binary blackhole pair (as seen by a nearby observer) spiralling around each other before they merge. Credit: Simulating eXtreme Spacetimes Lensing/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.